Kink University Tv Series the Art of Female Ejaculation How to Make Her Squirt 2014

From Fine art Journal 79, no. 1 (Spring 2020)

Drawing on the myth of Narcissus and the transgressive perversity it inspires, New York–based operation artist Narcissister embraces narcissism as an aesthetic and political strategy. The creative person, whose preparation includes classical trip the light fantastic toe and the fine arts, lives in a darkly humorous globe that consists of racialized dolls, mannequins, autoerotic sex play, and remarkable yet anticlimactic performances of synthetic archetypes. She is known for wearing an expressionless Barbie mask, wigs, and a kinky-haired merkin, all while concealing her "real" identity. Her live and video works feature a mix of titillating yet disturbing displays of penetration and versions of "the pullout method," which she performs on herself. In her art, edgy self-sex acts commingle with a multiplicity of characters and fictions typically considered taboo—kitschy soft-porn archetypes, topsy-turvy dolls, and mammies—to unsettle liberal ideas concerning multiracialism, feminist praxis, and virtuosity. Her contempo art features dolls with crudely assembled body parts à la Hans Bellmer and Cindy Sherman, cut-upwards masks of various skin tones, dysfunctional and ill-fitting costumes, and oversize props that oft thwart the artist'southward seamless execution of a choreographed step or cue. Specifically, her art extends formal strategies developed by Lorraine O'Grady, Carolee Schneemann, Adrian Piper, and Kara Walker to transform stereotypical imaginings of the female body and long-standing social and aesthetic debates almost the right and wrong ways to picture and perform racial and gender identity.

Narcissister's solo performances contain all the makings of psychosexual disorder, from multiple identities to kinky sex to cocky-objectification. Formally, she alters conventions of burlesque, African American concert dance, feminist craft (quilt making and collage), and camp (she paw makes her props and costumes from discarded materials). Thematically, she combines the visual histories of black subjugation with sexual transgression to highlight how these two phenomena, enmeshed since the eighteenth century, remain entangled in the early xx-offset century amid renewed interests concerning racial reconciliation and the promise of multiracial feminism.1 In so doing, she challenges the reparative expectations of fine art, activism, and multiculturalism in the mail–civil rights era.2 A self-identified "sister" of African American and Moroccan descent, Narcissister burlesques her own mixed-race heritage to stage self-objectification every bit the limit of multiracial promise.three

In name, the creative person plays with the polysemy of the word "sister," exercising the linguistic communication of racial and gender analogousness to redefine how we imagine community and solidarity in the early on twenty-kickoff century. She combines cocky-loving absorption with the idea of "sisterhood, especially amongst women of colour."4 By tethering narcissism to the history and memory of racial subjection, her otherness—her artful and corporeal alterity in terms of phenotype and athleticism—operates on ii levels. Narcissister's onanistic acts of incomplete functioning upend normative notions of mastery, on the one mitt, and black women's reproductive labor in the past and present, on the other. Inserting and expelling items from her genitalia is ane way the artist plays with these concepts vis-à-vis the boundaries of black and the trunk.

Because of her self-sexual activity radicalism and transgressive deployments of the body in performance, scholars and critics have lauded Narcissister's artworks as radical acts of redress and self-love. Ariel Osterweis and Barbara Browning consider her performances to be acts of reclamation and self-care that annul images of blackness women every bit degraded subjects.5 Arts and culture critic Priscilla Frank has called the creative person a "queer feminist superhero," while art critic Katie Cercone has likened Narcissister to a postracial feminist icon.six From these angles, the artist'due south creative endeavors recover the racialized, gendered self—restoring the historically subjugated body to some sense of wholeness and strength—through narcissistic sexual play. In my view, Narcissister'due south performance fine art gestures beyond the torso to question the limits of racial and gender identification as they have been thought inside identity-based art and its histories. The constellation of her background in African American concert trip the light fantastic toe, her training in black feminist craft and operation, and her participation in exhibitions comprising solely artists of African descent is peculiarly important here, as is her use of masks and various racial and sexual stereotypes typically ascribed to black women'southward bodies. Bridging her own complex racial and ethnic heritage with her artistic influences and practice, the artist unsettles narcissism'due south sexually perverse origins to focus on how pathologies of race, and specifically black, go along to energize our liberal imagination. Her work also underscores the myriad ways in which the visual economy of race and phenotype is also inherently sexual and libidinal.

The myth of Narcissus is the basis for the prevailing assay of narcissism, which Sigmund Freud characterized in 1914 as a sexual perversion wherein romantic attraction is directed exclusively toward one'due south self.vii This self-centering, typically understood as an extreme, pathological course of self-want, is thought to lead to cocky-affirmation and reassurance: narcissists love the self-image they project onto others, and when others reflect the projected image back, the narcissist's sense of self is affirmed. In this substitution, narcissists are reassured both of their existence and of the boundaries of their ego, a reflexive process that blurs all distinctions between reality and fantasy.

Beginning in the 1970s, narcissism became the nexus of a disparaging form of aesthetic criticism levied at feminist performance artists who used their own bodies in their alive and video art. Every bit Lucy Lippard observed at the time: "Men can utilise beautiful sexy women as neutral objects or surfaces but when women employ their ain faces and bodies, they are immediately defendant of narcissism. . . . Because women are considered sex objects, it is taken for granted that whatsoever woman who presents her nude body in public is doing then because she thinks she is cute. She is a narcissist, and [Vito] Acconci, with his less romantic image and pimply back, is an artist."8 Lippard's comments underscore the uneasy tension between feminism and self-display with which women artists at the fourth dimension were forced to contend. To counter this tension and the art earth's gender disparities, women artists and their critics claimed functioning also as narcissism as cocky-affirming sources of creative agency and representation.

For Amelia Jones, narcissism is a radical practice—when enacted by marginalized subjects, namely women artists, queer artists, and artists of color—that breaks downwards the self-other, mind-body separate unique to prevailing conceptions of modern subject field formation in the West. These binaries often characterize civilization and the heed as masculine, and nature and the body as feminine. Cocky-centeredness shatters this reductive view; in so doing, Jones explains, it becomes empowering. Rather than eclipsing women artists and the images and subjectivities they create, information technology elevates them, thereby expanding our agreement of feminism and art'southward appointment with social life.9

Just as self-centered functioning frustrates the art world's predominantly white, male, object-driven structures, Narcissister's art is expansive, crossing the boundaries betwixt entertainment, lowbrow dance, and fine art. "My interest in keeping my project broad and able to exist in many different scenes," she admitted in a 2014 interview with Joseph Keckler, "is unfortunately quite a liability. The feedback . . . from curators," she continued, "is that my artwork is too entertainment-flavored to be viable for them, and I don't take objects to sell. And the entertainment people often feel my piece of work is too arty, also opaque in its pregnant and standpoint, and too erotic for many 'amusement platforms.'"x To farther explore the possibilities of identity-based art and operation, Narcissister turned to caricatural. While completing the Whitney Independent Study Program in 2004–5, Narcissister found vibrancy in burlesque. However, the caricatural scene was limited to representations of white femininity and womanhood. "They still all basically wanted to be Marilyn Monroe," the creative person remembers.11 She, on the other paw, craved something more than versatile to conform nonnormative approaches to racial performance and eroticism. So she began disrupting the conventions of burlesque with handstands, reverse stripteases, and her masked dancing body. Narcissister's live and video works, yet, practice non build to sexual release or satisfaction, nor do they reveal or redress unknowable truths near sex, or race for that matter; they are essentially plastic and anticlimactic.12

Instead, the ways in which Narcissister flips in and out of costumes, multiracial masks, and apple-polishing sexual scenarios congeal into a kind of race play, a form of kinky sex that at once relishes yet exceeds erotic fetishism and fulfillment. Race play is a type of sexual fetish in which participants experience pleasance from re-creating racist and xenophobic situations drawn from history, such as Nazi-Jew interrogations, master-slave relationships, and public displays in which white interlocutors grease upwards and sell blackness bodies on the auction cake.13 Another dimension of race play is becoming aroused by the use of racist epithets and physical strength to demean one'south partner. It is a kind of psychological theater that gains appeal from its associations with any combination of the following: the desire to abandon responsibility, the desire to exist humiliated, self-hatred, the impulse to redress childhood trauma, or even to find or mimic spiritual connection. From the bespeak of view of race play, Narcissister's work complicates staid understandings of black and the body in gimmicky art and performance studies.

In gimmicky art history and performance studies literature, uses of the torso such equally Narcissister'south are typically read as a way to heal racial pain and injury. This understanding of performance assumes that it "offers a substitute for something else that preexists information technology," making the performing torso a proxy "for an elusive entity that it is not but that it must vainly aspire both to embody and to replace," in Joseph R. Roach's estimation.fourteen Performance, therefore, functions every bit a process of exchange, of standing in for something preexistent, lost, or elusive. In this procedure, the performing body is an effigy, Robin Bernstein tells us, "as it bears and brings forth collectively remembered, meaningful gestures, and thus surrogates for that which a community has lost."xv

Rather than affirmative cocky-dearest or redress, Narcissister'south antiredemptive enactment of self-sex bridges race play with Freud's pleasance principle, the instinctual search for pleasure and avoidance of hurting to satisfy biological and psychological needs.xvi Freud locates pleasure and pain on a spectrum, and Narcissister's cocky-effacing, apple-polishing sexual practice acts are situated at the bespeak where pleasure and hurting meet. But her practice of racialized BDSM (shorthand for bondage/discipline, dominance/submission, sadism/masochism) changes the terms of pleasance and hurting every bit they relate to power—domination and submission—and histories of racial and sexual subjection. Narcissister's race play exceeds any attempt to redress the trauma of racial subjugation in the past and present. Her brand of self-objectification undercuts social mores nigh sexual agency with enactments of self-inflicted discomfort, stalled orgasms, and bodily damage. In and then doing, her fine art foregrounds a relation betwixt racialized female sexuality and freakery that is distinctly irreverent and kinks up normative ideas about racial kinship and art'south liberatory potential. Moreover, latent within the creative person'southward race play is a social critique of the art world. The curious thing about race play is that in the broader fetish community, people of color pursue it, but more often than not the consumer base of operations is white, not dissimilar in the art earth.

Thus, instead of using senseless perversion or affirmative enactments of narcissism, Narcissister transmogrifies self-loving assimilation by adding a trivial kink to the mix. She strips, flips upside down, spreads her legs to reveal multiracial doll heads nestled in her crotch, and plays with herself, frenetically rubbing the masks and heads fastened to her torso and inserting and pulling items from her mouth, vagina, and anus. She moves quickly and gracefully. I blink and yous might miss something, like a swift costume alter or the climax we might expect from such a titillating brandish. Furthermore, Narcissister's conceptions and deployments of racialized stereotypes within and beyond the body contest black female person subjectivity in light of her own racial identifications as a "sister"—a woman of colour. Kink in this context spans curly wigs and merkins; sociocultural entanglements of race, gender, and sexuality; and crude forms of self-sex. The artist's cleverly suggestive moniker and kinky enactments of race play and self-objectification, as a result, recalibrate narcissism with regard to how racialized identities function in American public life.

In Every Woman (2008/9), Narcissister's best-known work, the artist reorders the striptease form by performing it in reverse. At the start of the video version of the slice, red curtains with gilded lining and black tassels part to reveal a nude Narcissister facing away from viewers as the photographic camera zooms to compress the frame and focus on the creative person's backside. Backside an eerie Barbie mask that conceals her identity, the artist revolves on a rotating platform similar to the kind circus performers use, making her nude body, brown-toned Barbie confront, and kinky-haired merkin visible from all angles. To Chaka Khan's "I'm Every Woman" (1978), she pulls clothing and accessories from her mouth, from between her legs, and from the oversized, kinky Afro wig she wears. Rather than serving as a revealing image of the artist, Narcissister's masking devices ensure that she is never fully exposed and that she instead presents an artificial structure. We feel the flipside of Chaka Khan's lyrics, "Annihilation you desire done baby/I do it naturally."17

Just as Every Adult female reverses the norms of caricatural, the work likewise contests the fictions and fantasies associated with black women's sexual desires and functioning. The Afro wig and pop song function as signifiers that call back the self-objectifying racial fictions of the blaxploitation film genre and racialized pornography of the 1970s and 1980s, the Golden and Argent Eras of erotic picture show, respectively. During this fourth dimension, blaxploitation and erotic films trafficked in exaggerated depictions of blackness women doing "it"—sex and sexuality—both exotically and "naturally," as Chaka Khan sings. The voluptuous, lustful blackness woman kicking ass in a huge, weapon-storing Afro and low-cut, impossibly tight habiliment is a recognizable and recurring stereotype in the one-time (Pam Grier as Coffy, in the 1973 film of the aforementioned proper name, for example). In the latter genre, lascivious black women who possess special "skills" and savour beingness racially subjugated in the sex act evince such fantasies. Narcissister'due south simulations of self-sexual activity in Every Woman and elsewhere, nevertheless, do not lead to cocky-affirming ecstasy; instead the orgasm is routinely displaced, frustrated, or quite literally fabricated in her work. Rather than mastery, incompletion—of sex, race, and reproduction also as trip the light fantastic-based virtuosity and fully knowable identities—is the peak of Narcissister'southward art, albeit counterintuitively.eighteen Her choreographed failures to climax, which appear as diverse forms of reversals and refusals beyond her practice, overturn early 20-commencement-century ideas about identity performance and multiracial futures. Narcissister's Afro wig and choice of Khan's late disco tune in Every Adult female are particularly important here because they elucidate how kink—from myths about black women'due south pilus to their sexual prowess—circumscribes black female person apotheosis in our putatively multiracial era.

Narcissister'south art coincides with but nevertheless refutes current American public discourse that valorizes multiracialism—ane of the greatest hopes and myths of the early twenty-start century. Writing on how The states news media link multiracial identity to contemporary racial norms, policy preferences, and cultural trends, communication studies scholar Catherine R. Squires observes, "Promoting tolerance and cross-racial intimacy at the dawn of the twenty-commencement century is much amend than the hysteria over race mixing that ushered in the twentieth. . . . That the mainstream printing is declaring a consensus that interracial marriage is a social good is no pocket-size alter."nineteen The American public's embrace of interracial coupling represents a movement away from centuries-old malaise nigh race mixing to promote tolerance, affirmative coalitional politics, and celebrations of cantankerous-racial intimacy as social goods. According to Squires, multiracial bodies are at present seen as harbingers of racial harmony rather than racial degradation, and this evolution is "evidence of some progress."20 These putatively progressive concepts are punctuated by the gains and failures of Barack Obama's 2006–8 presidential entrada and his 2009–17 occupation of the White House, important years for Narcissister's artistic evolution. Yet while representations of hybridity and multiplicity recur throughout her oeuvre, she repeatedly distorts idealized images of the mixed-race figure by performing its shortcomings.

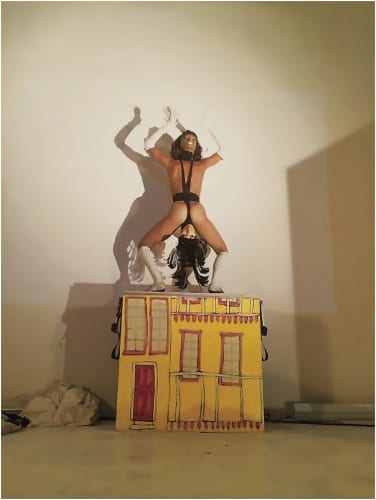

The Dollhouse (2011), also known as Upside Downward, exemplifies the artist's transformations of both narcissism and multiracialism. The Dollhouse has been performed at various lengths and at a multifariousness of venues, from the Box, a neoburlesque nightclub in New York City, to America's Got Talent, a prime-time idiot box diverseness evidence that airs on NBC.21 Equally a result, Narcissister has garnered a cult post-obit that spans queer gild civilisation, experimental film and performance, television, and the high-art world. At times preceded by a video set to eerie plant nursery music that features the artist's hands playing with a topsy-turvy doll in a multilevel wooden dollhouse, the alive performance piece of work opens with Narcissister wearing a brown-toned mask, a brown bob-fashion wig with bangs, and a red sailor dress. She is cloaked in a floor-length blue velvet hooded cape reminiscent of Cinderella, with long white gloves covering her hands and forearms. A large dollhouse prop is positioned upstage and center.

To the lyrics of "At the Crossroads," a vocal about a girl coming of age from the 1967 Hollywood musical Doctor Dolittle, Narcissister twirls, raises her gloved hands to the sky, and slowly kneels as if praying. Narcissister's gestures mirror the lyrics of the vocal: "Hither I stand at the crossroads of life/Childhood behind me/The future to come/And alone/Aught planned at the crossroads of life."22 She reaches far to the left and brings her hands to cover her masked eyes, her upper torso contracting and releasing in an action that resembles crying. She yearns for something: romantic dear and certainty most the future.

Then the music switches to a spare disco interlude, and Narcissister turns to face up upstage. She pulls her hood downwardly to reveal another chocolate-brown-faced mask attached to the dorsum of her caput. Her dress also has a dual identity, red with a sailor collar in the front, and a blue and brown paisley impress in the dorsum. She bends and disrobes before her two-headed "self" skips and prances across the stage, eventually transitioning into another costume change that takes place while she is upside down. Foreboding music signals that something strange is itinerant, and Narcissister delivers on cue as she bows her head to the floor and slowly rises into a headstand, pointing her feet. She pauses and so splits her legs dramatically to reveal a brownish dress and a third head—white with a black bob and bangs—popping upwardly betwixt her thighs. Her legs are now arms and her white knee-high stockings are at present gloves. She spirals her trunk, places her anxiety behind the doll head, and contracts her torso front and side. To stand, Narcissister rolls out of a backbend, thrusts her pelvis to the audience, plays with her third "self," and jumps up into a series of quick hip rolls.

The score changes to "Upside Down," Diana Ross's 1980 popular disco hit almost a adult female'south disorienting, self-effacing experience of romantic love, and Narcissister performs a dizzying sequence of acrobatic choreography.23 She flips in and out of handstands, strips topless, and turns to confront the audience. Suddenly aware of her exposure, she covers her bare chest with her skirt as the music changes to a synth version of "At the Crossroads." She scurries upstage and kneels every bit "Just the Two of Us" (1980), a more promising love vocal than "Upside Down," blasts through the speakers.24 Her feet walk up the dollhouse prop, and she is in one case over again in a handstand, this time with her back facing the audience. Her skirt tumbles to the flooring to reveal a black and gold embroidered apparel and nonetheless some other white mask erect betwixt her legs. Flipped upside down and inside out, she is now a ii-sided, four-headed, topsy-turvy doll, a toy made popular in the United States during the antebellum and postbellum periods.

Thought to have originated as an act of resistance and a production of black female slave labor in the antebellum Due south, the topsy-turvy doll became a symbol of miscegenation. It simultaneously emblematized racial fusion, cross-racial intimacy, racial bureaucracy, and sexual violence.25 The two halves share a waist and a skirt, and when the doll is flipped, either the white or blackness end is visible, a playful act of appearance and disappearance that Narcissister deploys in The Dollhouse. These actions contain inside them the thought of racial flip-flops, the promise or threat of total racial transformation—white to black and vice versa—at the expense of racial concealment. As Robin Bernstein explains, "If ane side of the topsy-turvy doll is exposed, the other side lurks, waiting, beneath the skirts."26 Though the flip of the skirt invites play, "The affair determines that [the doll's black and white] poles never collaborate, and that one grapheme always obliterates the other," making racial marriage both contingent yet impossible—a kinky entanglement.27

Confronting this backdrop, Narcissister'southward The Dollhouse bridges interracial desire with popular American movie, music, and material civilisation. Her embodied version of the topsy-turvy doll ultimately refuses racial integration, keeping the masks side by side yet separate and apart. In then doing she joins the failure to accomplish cocky-realization through sexual ecstasy with racialized imperatives to biologically reproduce. Her body and movements not but highlight how coupling and futurity energize the American racial imaginary in the post–civil rights era; they also challenge the myth of happy "coexistence" in a society where racial others are inexorably dominated, enslaved, and violated. Narcissister'southward mixed-race, sexual, dancing body is the doll—the thing—that prevents the two poles and four faces from coming together. There is no racial harmony here, and it is on and through her body that racial spousal relationship, or miscegenation, is foiled.

With The Dollhouse, Narcissister crudely choreographs fantasies of miscegenation in order to thwart them, and her refutation of cantankerous-racial intimacy is made clear in the piece'southward final minutes. The creative person climbs on elevation of the dollhouse and gain to strip down to a sexy black singlet. Standing, she contorts her body, angle frontwards and astern to permit the faces on each end and side of her to alternately gaze at each other. Her hands caress her many doll heads, and she throws dorsum her actual head to register momentary pleasure. The unsuccessful union of the paired faces on Narcissister'south forepart and back, however, attenuates this moment. They are stuck in intimate contact but separated by the artist'southward body, a fraught however fixed estrangement that prevents them from realizing the physical encompass, or cocky-affirming climax, for which they long.

The end sequence caricatures the mythos of cocky-love and self-discovery that organizes prevailing visions of postracial, postfeminist futures, a facet of the artist'southward functioning that typically eludes her critics. In Katie Cercone's review of The Dollhouse, Narcissister "is the integrated cocky. . . . She is swiveling, wheeling; a fallacious icon of a raceless, genderless, classless hereafter feminism to come."28 This assessment echoes the reparative undercurrents of ceremonious rights and feminist soapbox, which Cercone extends to a postracial, postgender, postclass future. Just Narcissister'southward autoeroticism defies this logic. While she is temporarily excited by the myriad options available to her, the frenetic costume changes, acrobatics, vaudevillian trickery, and multiracial dummy faces do not culminate in anything resembling integration, racial utopia, or a satisfying sexual union. Neither she nor the desires of her plastic, multiracial doppelgängers, personified past the lyrics "Just the two of us/We tin can get in if we try," are fulfilled.29 She besides brings to life the historically disturbing topsy-turvy doll, demonstrating its current symbolic relevance.

In animating the two-headed doll and flipping betwixt racial poles, Narcissister disorders our sense of what is real and what is non in terms of pleasance and the torso's racially and sexually expressive potential. This act of subversion as well satirizes twenty-commencement-century sensibilities regarding multiracial figures as evidence of national progress. From these vantage points, The Dollhouse eschews common understandings of multiracialism, which uphold heterosex and romantic intimacy equally sites where racial disharmonize, even estrangement, tin be suspended or dissolved.thirty In Amalgamation Schemes: Antiblackness and the Critique of Multiracialism, critical theorist Jared Sexton explains how multiracialism and normative sexuality structure contemporary social relations.31 Despite beingness heralded as the post–civil rights answer to racial strife, multiracialism, co-ordinate to Sexton, reinforces anti-black sentiment and sexual norms past evoking long-standing tenets of each while purporting to do away with them. Those who promote multiracialism every bit a cornerstone of progressive social change misrecognize the violent legacies of slavery and its afterlives to which race mixing is tethered, namely the sexual violence endured by slaves at the easily of slave owners. Historically, in the Us context, offspring from interracial sexual reproduction presume the lower condition of the black, typically maternal, parent. Hypodescent—the automated assignment of racial status—is the basis of the one-driblet dominion ("ane drop" of blackness claret), a social and legal principle that evolved during the nineteenth century and was codified into police force in the twentieth. Racial classification based on blood breakthrough gave rise to phenomena such as racial passing, racial purity, and moral panic over maintaining that purity in the antebellum and postbellum periods.

While nosotros no longer live in a time when interracial marriage is illegal, or when tropes of mixed-race identity such as the tragic mulatto circulate widely, Narcissister'due south topsy-turvy performance illustrates that anxieties concerning racial authenticity persist in the present.32 Almost importantly, her employ of multiple masks that visualize varying phenotypes highlights the uncertain promise of postracial integration. From life-size dolls to doppelgängers and embodying every woman, the artist overturns early twenty-start-century aspirations for racial and sexual transcendence as culturally compensatory exercises. The artist's chosen props—dolls, masks, and double identities—further evince the undoing of a mail-identity future through engaging Freud'due south theories of the "double" and the uncanny.33

Narcissister's mobilization of the double and the uncanny puts race and gender at the heart of Freud's psychoanalytic theories by generating feelings of revulsion in response to things and notions of identity that are familiar, but slightly off. Additionally, doppelgängers in Western art and its histories take represented the divided cocky, assuasive artists to explore myriad personas and limited experiences of otherness and crunch.34 Alternatively, dollhouses, dolls, and the gendered play they inspire are signs for human development and futurity. For Freud, the uncanny'south mixture of the familiar and the eerie confronts subjects with their own unconscious, repressed impulses.35 Dolls, specifically, he explains, are imbued with living qualities, and equally children, we treat dolls equally if they are alive. Through interactions with such objects, children receive information most social relations and cultural norms concerning adulthood and domestic life. Narcissister upsets this progressive arc and assumptions almost the ends of racial mixing and sex activity by reproducing not children, merely rather kitsch and multiracial plastic masks that do not find themselves in blissful spousal relationship. Furthermore, Narcissister's self-objectification—performing every bit a masked dancing doll that both mirrors and animates the props and effigies she employs—troubles the boundary between blackness and white, person and thing, equally well as the line between pleasure and pain.36 In and so doing, she refigures normative conceptions of identity, objecthood, and ultimately humanness by transposing narcissism from self-loving absorption to cocky-objectification.

Narcissister'southward 2015 evening of alive and video functioning titled "Weather of the White Mask" expands the scope of race play on offer in The Dollhouse. Included in Simply Like a Woman, a festival copresented by the Abrons Arts Center in New York on Oct 24, 2015, "Weather of the White Mask" circles back to the doll every bit an object of terror, racial intimacy, and pleasure. Just rather than an outright refusal of cross-racial intimacy, "Atmospheric condition of the White Mask" sets in motion an intimate relation between whiteness and blackness that Ariane Cruz argues is vital to racialized women'south enactments of BDSM and erotic fantasy.37

Babe Lady (Forever Young), the first of the evening'south live works, opens with Narcissister hiding under a suitcase that is dressed as a bassinet. The bassinet holds a white baby doll. Set to Alphaville's "Forever Young" (1984), Baby Lady depicts the phases of (white) womanhood from birth to death.38 Narcissister scuttles out from under the bassinet on her knees, cloaked in blackness and wearing a white Barbie mask. A blond, toddler-size daughter doll in a white lace clothes is attached to her confront. Abruptly, Narcissister stands, turns, and pulls the doll downwards for a quick change. A bigger doll with crimped curls is attached to her back, which now faces the audience. Side by side, she is an older version of the doll, wearing pigtails and a pinkish apparel bloodstained in the back. Between graphic symbol changes, she inserts dance moves—an arabesque turn, a chassé—gracefully transitioning from one stage of womanhood to the adjacent. She plays softball in overalls. She marches downwards an imaginary aisle, kickoff in a blackness graduation gown, and then in a pink nuptials dress and veil. "Adjacent comes baby and the baby railroad vehicle," as the saying goes, and this is where things go kinky.

She strips to breastfeed, and after placing the doll dorsum in its buggy, she pushes information technology away and pulls two gray, braided pigtails from her anus. The grayness pigtails replace the blonde ones as she slips into a unlike pink dress, circles the stage, and stops to "birth" a wrinkled mask from her vagina, which she fastens to her already masked face. She is now an elderly white woman, dropping her pigtail sideburns for the wrinkled face up. To terminate, she crawls back under the suitcase and reveals its contents to the audience—her gray-haired doppelgänger in a satinlined coffin—before resetting the suitcase to the bassinet.

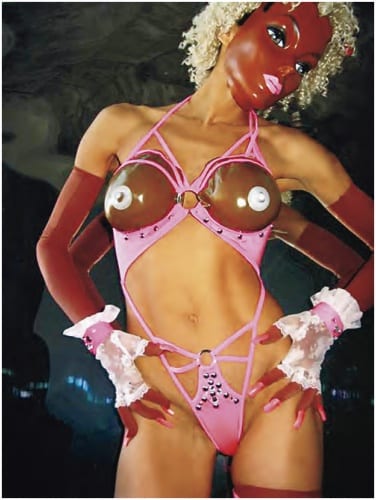

Infant Lady's depiction of the developmental phases of white womanhood sets the stage for the complementary set of works near sex, race, reproduction, and romantic love that follow. In each piece, Narcissister'due south torso subverts conventional narratives associated with homo evolution and cross-racial intimacy. The beginning video of the evening, Man/Adult female (2009), stars a frustrated white fanboy. "Photograph," Def Leppard's 1983 pop-metallic rock ballad, plays in the background.39 It is a song almost a sex symbol akin to Marilyn Monroe who is just out of reach and whose visage is reproduced in pictures. Throughout, still and moving images of Marilyn Monroe, "the blonde bombshell," populate the vocal's music video. But Monroe is non the fanboy's fantasy in Human/Woman. In his cramped, cluttered sleeping room, the fanboy flips through Blackness Tail, an adult fetish magazine specializing in photographs of blackness women's backsides. On his already porncovered wall he hangs a centerfold affiche of his chosen slice: a curly blonde Narcissister in a nighttime-dark-brown mask with matching breasts.

The white fanboy caresses the image of Narcissister and excitedly pulls out his Johnson to stroke and pleasance himself. In the human action, he discovers a dark layer of pare and long pink nails underneath his ain white "skin." Then the live Narcissister emerges, turning out the props meant to signify the white fanboy's person from the inside and arranging his wear, hair, face, and breast on the bed. Wearing the mask, wig, and breasts from the poster forth with a white strap-on over a pink G-string, the "real" Narcissister wildly rides the fanboy's remnants—dildo and all—to no avail. His parts practice not hold up under her rigorous grinding; they literally fall apart, thus failing to satisfy her. Feigning disappointment, in silence she discovers her prototype in ii facing pages of Black Tail and masturbates using the fanboy's now detached, silicone member, climaxing and leaving him behind.

In the next video, 18 Heads, Narcissister is a double-headed Marie Antoinette searching for her perfect complement. She tries on multiple heads that run the gamut from a greenish monster mask to the head of a woman conveying a basket of fruit on her head. Post-obit the fate of the infamous queen of France, those that do not fit her standards are guillotined. Finally, Narcissister finds the perfect mate to complete her: a matching Marie Antoinette head of a slightly darker hue.

In the terminal piece of the evening, Unforgettable, the creative person dances in a tuxedo to Nat King Cole'south eponymous carol before stripping downward to blackness lingerie.40 Next, she stages what appears to be a romantic tale of boy-meets-girl using two stake-colored puppets; the male is dressed in a elevation hat and tuxedo jacket, the female in a silvery blouse. Dissimilar in a traditional boob testify, where puppeteers' arms bring characters to life amongst made sets and curtains, Narcissister lies on her back and uses her legs and feet equally the puppets' base. In and then doing, she transforms her scantily clad body and blackness-lace-covered legs into a table where the puppets dine and admire ane another to the sounds of Rihanna's "Birthday Block."41 To create a romantic atmosphere, the creative person inserts a long-stalk candle into her vagina. Other props such equally fake wine spectacles, a block, and a smokeless sparkler candle complete the festive scene. In the end, the puppets smooch and embrace.

Taken together, the diverse events of "Conditions of the White Mask" reveal a great deal about the mores of contemporary identity discourse, womanhood, and cross-racial intimacy. They expose not only the sexual dimensions of race simply as well how multiracialism is imbued with heteronormative pronouncements such equally love, romance, family, marriage, and reproductive futurity. "Conceptions of the multiracial cannot aid but imply a production of race in the field of heterosexuality, nominating, more specifically, the reproductive sexual activity human action every bit the chief site of mediation for racial difference itself," Jared Sexton explains.42 As a result, the fruits of amalgamation become part of a reformist schema in which the future multiracial kid is recruited to recuperate a traumatic past marked past unique forms of racial terror and to pave the manner for a racially transcendent time to come.

By contrast, Narcissister burlesques her own mixed-race heritage as well as public debates concerning the biopolitics of interracial intimacy and its transformative potential when, instead of babies, she pulls a wrinkled mask from her vagina and constructed braids from her anus in Baby Lady. As Narcissister alternately assumes an identity every bit a table, as a candle stand, as sparkling amusement for the adoring puppets, and as a sex freak for the audience in Unforgettable, selfobjectification is the limit of multiracial promise for Narcissister. Thus, rather than "a deployment of sexual divergence through which the seeming transgression of race mixing is resolved, start into the 'romantic complexity' of courtship and wedlock, and then into the reproductive futurity of the 'mixed-race' kid," as Tavia Nyong'o observes, Narcissister performs reproduction without futurity.43

Furthermore, "Conditions of the White Mask" deepens the artist's conceptual date with feminist art's gimmicky currency by transmuting the expectations of the racialized virtuosic body explored in earlier works to embodied ambivalence toward both multiracialism and white womanhood. Instead of an imagined customs of boundary-crossing hybrids who redeem the trauma of black subjugation in the by, present, and future, Narcissister's performances against multiracial possibility result "in a representational space that is both black and, in a specific sense, negative," as Nyong'o puts information technology.44 This black, negative space "cannot spell out a set of instructions on how to bear ourselves in the present, but can only instruct against the presumption that its stories prevarication at the ready to be told."45 To this finish, Narcissister's nonprocreative sexual practice play brusk-circuits the rationales of both multiracial exceptionalism and the promotion of packaged family values vis-à-vis domestic coupling, two-parent households, and the nuclear family unit. This reveals two things: one is the true aspiration of multiracialism, which is the singularity of blackness as a social identity, a political organizing principle, and an object of want, to paraphrase Sexton. The other is a refusal of the social and aesthetic norms apropos what is appropriate when it comes to racial representation and sex in the twenty-offset century.46

Finally, Narcissister's refusal to reveal her "real" identity, her use of parody and pastiche, and her performances of crude, anticlimactic sexual practice transform egoloving cocky-absorption into something else altogether. In the story of Narcissus, the mythological antihero searches for a worthy object of desire, refusing all who court him. To Narcissus, his suitors fall short of his expectations, including Echo, who, cursed by Zeus's wife Hera, is unable to speak her love for the ill-fated hunter. When she reveals her identity and attempts to cover him, Narcissus rejects her, and she fades away, but her phonation remaining.47 Eventually, Narcissus "finds himself" when Nemesis lures him to gaze into a pool of water in a secluded, dark meadow. In his reflection he discovers the love object for which he has been longing: himself. Transfixed by his own image, Narcissus stares at his reflection until he realizes his dearest can never exist reciprocated, whereupon he commits suicide.

Though arrogance and vanity band true of narcissism, misrecognition, non mere self-loving absorption, leads Narcissus to choose himself as a love object. In endeavoring to complete his joining of himself to his beloved-image, he forgets himself entirely, foregoes relations with others, and ends his life. In then doing, Narcissus eschews culturally determined forms of sociality past forestalling a self-affirming future conventionally secured through romantic love, coupling, and procreation. This antirelational thrust and curt-circuiting of social norms are at the heart of Narcissister's performance practice. But the artist's irreverence propels narcissism and the concept of antirelationality into new territory.

Different Narcissus, the center of the artist's affected narcissism is not a beautiful, white, male person figure effectually which much of the literature on antirelationality has been organized. In queer theory, antirelationality emerges from queer, white, cis-masculine critiques of heteronormative injunctions that center on the child, whereby biological reproduction determines and evidences our output and social potential.48 That is, our productivity is linked to our reproductive capacities, and political possibility is tied to building meliorate futures for our children. For Lee Edelman, writer of No Future: Queer Theory and the Expiry Bulldoze, the logic of "reproductive futurism" presupposes three things. Information technology suggests: showtime, that the hereafter has "unquestioned value and purpose"; 2nd, that we can amend it; and, 3rd, that the future is emblematized by the child.49 Every bit such, reproductive futurism renders unthinkable all alternatives to kinship and solidarity.

Critical race- and operation-studies scholars such equally Amber Jamilla Musser, Roderick A. Ferguson, Tavia Nyong'o, and José Esteban Muñoz accept constitute fault with this line of thinking, arguing that queerness is neither counter to hope nor solely the domain of white cis men. For these authors, racialized subjects, and black subjects in particular, are always already against or exterior the norm. Because of these social weather condition, minoritarian subjects cannot beget to turn away from the political possibility of communal world making. In this schema, queerness engenders utopian forms of existence and belonging in the present that produce, according to Muñoz, "a type of melancholia excess that presents the enabling force of a forwards-dawning futurity."l Minoritarian subjects, in other words, non only need hope and alternative configurations of futurity; they forge these conditions in social club to persist and thrive under and against oppressive forces.

Narcissister reconfigures narcissism's associations with homoerotic want and feminist omphalus-gazing and redirects the white male person origins of antirelationality. Her art also moves beyond the need for hope and future into a world where dissociation and disaffection are preconditions of black female embodiment and being. The artist's cocky-identification and kinky performances of race, gender, and sex make this provocative and necessary shift more than complex. Neither her creative labors nor her make of self-objectifying narcissism can exist extricated from her clashing racial identification because they are both confining and complicated by multiracialism'southward problems and pitfalls. Narcissister's donning of multiple selves, and then, is more than mere performance meant to redress racial and gender wounding. Her performances depict our attention to the pornotropic fields—of vision and theory—that constrain her body and her artistic practice. The artist'south nonprocreative sex play upends prevailing ideas about our present and future by demonstrating how racialized bodies keep to function every bit ciphers for social and sexual relations. Her piece of work foregrounds how a sexual act is e'er inevitably fraught with race and that self-objectification tin can constitute self-love and cross-racial intimacy, sometimes necessarily then. She is, to put it simply, a truly kinky artist.

Tiffany E. Hairdresser is a scholar, curator, and critic of twentieth- and twenty-kickoff-century visual art, new media, and operation. Her work focuses on artists of the black diaspora working in the The states and the broader Atlantic world. She has published widely on African American art, fashion, trip the light fantastic, and engineering. Barber is assistant professor of Africana studies at the Academy of Delaware.

Source: http://artjournal.collegeart.org/?p=13330

Post a Comment for "Kink University Tv Series the Art of Female Ejaculation How to Make Her Squirt 2014"